Featured

How genetics and social games drive evolution of mating systems in mammals

By Tim Stephens

UC Santa Cruz

January 7, 2020 — Santa Cruz, CA

(Photo above: Yellow-bellied marmots — Marmot flaviventris — at the Rocky Mountains Biological Laboratories in Colorado. This species has a polygynous mating strategy that evolved from a monogamous ancestor. Credit: Ben Blonder)

From monogamy to promiscuity, a new model explains the evolution of diverse mating systems based on the conflict between cooperative and competitive behaviors

Traditional explanations for why some animals are monogamous and others are promiscuous or polygamous have focused on how the distribution and defensibility of resources (such as food, nest sites, or mates) determine whether, for example, one male can attract and defend multiple females.

A new model for the evolution of mating systems focuses instead on social interactions driven by genetically determined behaviors, and how competition among different behavioral strategies plays out, regardless of external factors such as defensible resources. In this model, social interactions can drive evolutionary transitions from one mating system to another, and can even drive a population to split into two separate species with different mating systems.

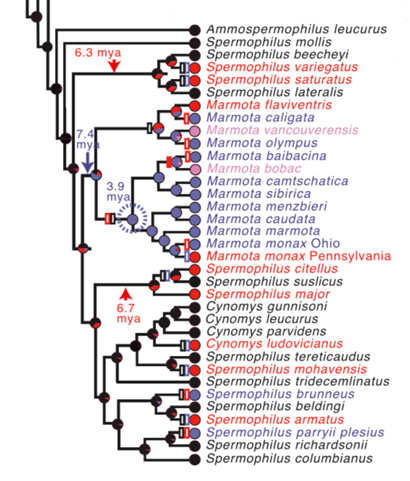

A portion of the phylogenetic tree of the squirrel family (Sciuridae) illustrates how promiscuous ancestral species (black dots) gave rise to both monogamous species (blue dots) and polygynous species (red dots). Marmots (genus Marmota), for example, are mostly monogamous, although there are a couple of polygynous species. Ground squirrels in the genus Spermophilus include promiscuous, polygynous, and monogamous species. (Credit: Sinervo et al., Amer. Nat. 2019)

The model is based on three fundamental behavioral strategies: aggression, cooperation, and deception. The conflict between competitive and cooperative social behaviors drives the evolution of the mating systems. In a paper published December 18 in American Naturalist(online ahead of print publication in the February issue), researchers compared the predictions generated by this model with published data on the mating behavior of 288 species of rodents.

“By and large, everything in our predictions seems to be borne out in rodents,” said first author Barry Sinervo, professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. “Our model is a universal equation of sorts for mating systems.”

The evolutionary story that emerges from the study goes something like this: An ancestral population of rodents is promiscuous in its mating behavior. Genetic variation within the population results in individuals with distinctive behaviors. Some males are highly aggressive, defend large territories, and mate with as many females as they can. Others are not territorial, but sneak onto the territories of other males for surreptitious mating opportunities. And some are monogamous and defend small territories, cooperating with neighboring males at territorial boundaries.

Continue reading here: https://news.ucsc.edu/2019/12/mating-systems.html

###

Tagged Baskin School of Engineering, Genomics Institute, UC Santa Cruz