Featured

What do community college students gain from engineering abroad programs?

By Jo-Ann Panzardi, Chair of the Engineering Dept at Cabrillo College,

Xitlali Galmez and Kurt DeGregorio, students at Cabrillo College

February 4, 2020 — Aptos

Abstract

The EA Program consists of a four phased model: (i) application process; (ii) preparation fall semester 2-unit ENGR 98A Global Engineering course building team spirit, studying Guatemala’s culture, politics and economy; learning about travel and worksite health; and conducting preliminary design for the abroad project; (iii) two-week engineering service-learning 1-unit ENGR 98B Engineering abroad course in Guatemala during the winter session working alongside community members in designing and building community-directed projects; (iv) reflection spring semester weekly meetings delivering presentations and papers on the experience to the Cabrillo College community, local engineering organizations, and at ASEE and Society of Professional Engineers (SHPE) conferences.

This paper presents both quantitative and qualitative obtained from the 2013-2017 abroad programs. The quantitative data was collected in the form of pre and post self-assessment surveys and institutional retention and transfer data. In the self-assessment surveys, students rated their industry skills, civic engagement, global cultural skills, personal and academic growth, and engineering skills based on Purdue University’s Engineering Projects in Community Service (EPICS) Program with a scale of 1 (low) to 10 (high) scale. There was an overall average increase from 6.84 to 8.80, resulting in a 28.7% increase in the students’ perceived skill set. The retention and the transfer rates of the abroad students were compared to a matched comparison group using Propensity Score Matching. In both instances, the EAP student outscored the comparison group by 27% in retention rates and 33% in transfer rates. Qualitative data was collected through focus groups and interviews of EA participants and surveys of abroad alumni. The Cabrillo Engineering Abroad Program has made and continues to make an impact on engineering students, enhancing their abilities and empowering them on their educational career path.

Cabrillo College

Cabrillo College is a public, comprehensive two-year Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) and member of the California Community College System. The college is located in Aptos, CA in Santa Cruz County, pop. 275,897 (2017 ACS), along the north central coast. In Fall 2017, Cabrillo College enrolled 12,242 students with 44% being Latino/Hispanic (an increase of eight percentage points in the last five years), 45% Caucasians, 3% Asians, 1% African Americans, 1% Filipinos, 0.5% Native Americans, 0.5% Pacific Islanders, 1% unknown, 4% multiple ethnicities. In addition, almost one-third of first-time students are first-generation college students and 52% of students are designated as low-income as defined by the national standard of family income below 150% of the poverty level.

Cabrillo serves Santa Cruz County and draws students from north Monterey and west San Benito Counties. To the north of Cabrillo College is the Silicon Valley and the greater San Francisco Bay Area with their high-tech industry and multiple four-year public University of California (UC) and State Universities (CSU). To the south is the city of Watsonville, the center of a productive agricultural region that is rich in cultural/ethnic diversity, but also characterized by low levels of education attainment, high seasonal unemployment, and low per capita income.

Out of the 114 California Community Colleges, Cabrillo is in the top 12% per capita in the number of students transferring to the University of California system (2016-17). The percentage of Cabrillo’s transfer students who are from underrepresented groups has grown from about 20% in 2000 to 40% in 2017.

Engineering Department

Cabrillo College’s engineering program was established in 1960 in the second year of the college’s operation. It presents a complete lower division engineering program, which prepares students to transfer and successfully complete a baccalaureate degree in engineering. Cabrillo College’s engineering coursework follows a pattern established by the California Engineering Liaison Committee (ELC), the statewide engineering education organization. Cabrillo engineering has been a major player in this group for more than half a century.

Cabrillo College has seen a growth of 135% in the number of engineering majors from 2012-2013 to 2017-2018. The Engineering Department has strong ties with California public and private universities through maintenance of more than 300 articulation agreements. According to the data collected by the National Student Clearinghouse for 2013-17, the Cabrillo engineering department ranks seventh in the college in the number of students who transfer each year and ranks second among all the STEM programs. Cabrillo does an excellent job in preparing students to be successful upon transfer to four-year institutions. According to the GPAs of junior-level engineering students collected by San Jose State University’s College of Engineering, engineering transfers from Cabrillo College outperform transfers from all eighteen other community college.

Engineering Abroad Program

Launched in 2013 and inspired by Madison Area Technical College Renewable Energy for the Developing World program and Purdue University’s EPICS program, the Cabrillo College Engineering Abroad (EA) Program initially served 11 students. With the 2014 NSF EAGER support project “Strengthening Student Commitment through an Engineering Abroad Program” (#1446430), the program used lessons learned from the pilot phase to evaluate the impact that a full-year engineering abroad program has on community college engineering students.

Engels1 reviewed study abroad programs from various universities and concluded that “there are higher retention and graduation rates [among student abroad participants] compared with students who do not study abroad.” Unlike these programs, Cabrillo’s EA Program provides a service-learning (not “study abroad”) abroad opportunity to financially at-risk and traditionally underrepresented community college engineering students. The goal of the EA program are to determine the impact that (1) a design/build engineering service-learning project and (2) an abroad experience is in a Spanish-speaking country have on low income and traditionally underrepresented students, particularly Latinx since more than 40% of the Cabrillo engineering student population is Latinx.

The EA Program consists of a four phased model: (i) application process; (ii) preparation fall semester 2-unit ENGR 98A Global Engineering course building team spirit, studying Guatemala’s culture, politics and economy; learning about travel and worksite health; and conducting preliminary design for the abroad project; (iii) two-week engineering service-learning 1-unit ENGR 98B Engineering abroad course in Guatemala during the winter session working alongside community members in designing and building community-directed projects; (iv) reflection spring semester weekly meetings delivering presentations and papers on the experience to the Cabrillo College community, local engineering organizations, and at ASEE and Society of Professional Engineers (SHPE) conferences.

Abroad Experience

Cabrillo’s engineering abroad experience is a two-week, in-country program consisting of engineering service-learning projects and cultural exploration. The two faculty coordinators accompany ten-to-fifteen students and one peer leader.

During the design of Cabrillo’s first EA program, Dream Volunteers in Mountain View, California was selected as the non-profit, non-governmental organization we partnered with. Dream Volunteers identified Vuelta Grande (VG), Guatemala as an appropriate community who can benefit from student-run engineering projects. VG is a rural hillside village of 120 families just outside the city of Antigua. It is an indigenous farming community that lacks common infrastructure. Young girls are tasked to help with day-to-day chores, which include hiking many miles a day to retrieve water and young boys work in the fields. The community identified access to water as their greatest need, so the first abroad program designed and constructed a rainwater catchment system. However, upon closer examination during the second year’s preparation, we discovered the village’s need was a water storage system tied into their spring and well with a means to remove sediment. Five years of the engineering service projects resulted in VG increasing its water storage capacity from 500 to 19,000 gallons. In addition, other projects completed include re-grading their community soccer field, which was in danger of eroding away, construction of a computer classroom, several retaining walls at the local school, and many smaller maintenance projects in and around the community.

Assessment and Evaluation

The multi-year assessment and evaluation was conducted on four EA Program cohorts (2013-14 through 2016-17) with a total of 49 participants varying in engineering majors and student classification: some having one more year at Cabrillo prior to transferring and some being in their last year prior to transferring. The demographics of the participants are shown in Table 1 with the majority of students being low income and over half being under-represented minorities (URM). The URM designation includes African American, Filipino, Latino, Native American/Alaskan Native, Pacific Islander, and Multi-Ethnic students. The URM designation excludes Asian, White, and Unknown/Non-Respondent students.

Table 1. Engineering Abroad Participant Demographics

| EAP Cohort | Total Students | Average Age (years) | Median Age (years) | % Female | % URM* | % Latino | %

Low Income |

%

Engineering Majors |

Avg. Starting

GPA |

| 2014 | 11 | 28 | 23.5 | 36% | 36% | 27% | 91% | 100% | 3.16 |

| 2015 | 14 | 22 | 20 | 29% | 50% | 43% | 64% | 100% | 3.20 |

| 2016 | 14 | 22 | 20.5 | 29% | 57% | 50% | 93% | 100% | 3.19 |

| 2017 | 10 | 23 | 23 | 60% | 60% | 40% | 100% | 100% | 3.34 |

| Overall | 49 | 24 | 22 | 37% | 51% | 41% | 86% | 100% | 3.22 |

Formative and summative assessments were completed utilizing quantitative and qualitative techniques. The quantitative techniques included self-assessment surveys and comparisons of institutional retention and transfer data. The qualitative techniques included focus groups and interviews with the EA participants and surveys of abroad alumni.

Quantitative Assessment

For the self-assessment surveys, EA participants completed pre- and post-program surveys to measure their perceived level of personal and professional growth before and after the abroad program. The assessment instrument was adapted from Purdue University’s Engineering Projects in Community Service (EPICS) Program. Students rate themselves on a scale of 1 (low) to 10 (high) on the industry skills, civic engagement, global cultural skills, personal and academic growth, and engineering skills shown in the appendix. The results are shown in Figure 1. The perceived growth was 30.9% in industry skills, 26.1% in civic engagement, 32.6% in global cultural skills, 22.0% in personal and academic growth, and 32.7% in engineering skills resulting in an overall average increase of perceived skill set of 28.7%.

Figure 1. Pre I / Post II Means by Construct for All Participants

*Differences are statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level

For the comparison of institutional retention and transfer data of the EA participants, a statistical analysis was conducted to compare the retention and transfer progress of EA participants to a matched comparison group using Propensity Score Matching (PSM). EA students were matched to non-EA engineering majors based on student-level characteristics and academic performance prior to and during the EA spring application term (one primary semester before the start of the EA program). Each EA student was matched to three comparison students based on gender, ethnicity, income level, cumulative grade point average (GPA), and total engineering units earned with a ‘C’ grade or better through the spring application term. The final comparison group consisted of 147 students.

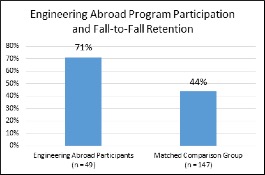

Fall-to-Fall Retention Data

Figure 2 shows the results of fall-to-fall retention of the EA students compared to the matched comparison group.

Figure 2. Marginal Means for the Effects of Engineering Abroad Program Participation on Fall-to-Fall Retention

| +27* |

*Differences are statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level

The post-regression adjusted means show that 71% of EA participants enrolled in at least three consecutive semesters after the start of the program compared to only 44% of the comparison students (p < 0.01), a difference of 27 percentage points. Participation in the EA Program was the most significant predictor of fall-to-fall retention in the regression model.

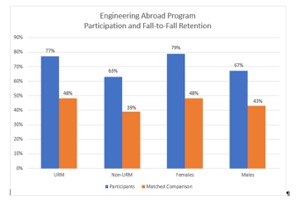

The fall-to-fall retention rates were also examined for each of the following groups: URM, non-URM, females, and males, and are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Marginal Means for the Effects of Engineering Abroad Program Participation on Fall-to-Fall Retention for URM, non-URM, females, and males

For the URM EA participants, the fall-to-fall retention rates were significantly higher than URM engineering majors in the matched comparison group, a difference of 29 percentage points. More than three-quarters (77%) of URM abroad participants enrolled in three consecutive semesters compared to just under half (48%) of all comparison students.

For non-URM EA participants the difference in fall-to-fall retention was 24 percentage points higher than non-URM students in the comparison group. While 63% of non-URM abroad participants enrolled in three semesters, only 39% of non-URM comparison students returned the following fall semester.

Similar to URM students, female students had an overall higher retention rate than male students, regardless of participation in the EA Program, and EA participants had higher rates than non-participants. An examination of retention rates by gender and EA participation showed that almost 80% of female EA students persist through the following fall semester compared to roughly half (48%) of females in the matched comparison group (+31 percentage points).

For male EA participants, the fall-to-fall retention rates were 24 percentage points higher than that of non-participants (67% vs. 43%, respectively).

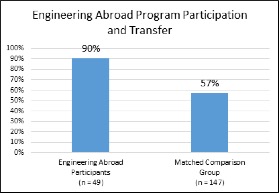

Transfer/Transfer Ready Data

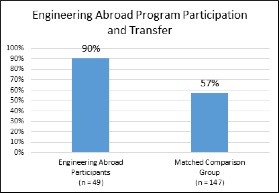

Figure 4 shows the transfer data collected from the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) of the EA students compared to the matched comparison group.

Figure 4. Marginal Means for the Effects of Engineering Abroad Program Participation on Transfer to Four-Year College

| +33* |

*Differences are statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level

EA participants are significantly more likely to transfer to a four-year college and/or become transfer ready than comparison students (90% vs. 57%, respectively, p < 0.01). Transfer ready means students have completed transfer-level math, transfer-level English, 60+ transferrable units, and have a 2.0 GPA or higher. The overall effect of EA participation resulted in an increase of 33 percentage points on students’ transfer rates.

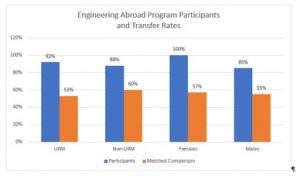

The transfer rates were also examined for each of the following groups: URM, non-URM, females, and males, and are shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Marginal Means for the Effects of Engineering Abroad Program Participation on Transfer to Four-Year College for URM, non-URM, females, and males

The URM and female EA participants had the greatest increase in transfer rates over the comparison group of all the subgroups examined in this analysis (+39 percentage points and +43 percentage points, respectively). All but two of the URM EA participants transferred or were transfer ready (92%) compared to just over half (53%) of the URM students in the matched comparison group. For non-URM students, 88% of abroad participants transferred or obtained transfer ready status compared to just 60% of non-participants (a difference of +28 percentage points). The difference in transfer rates by gender for EA participants ranged from 85% for males to 100% for females compared to roughly 57% for non-participants.

Qualitative Assessment

The qualitative techniques included EA participant focus groups and interviewing the participants three times during the EA Program:

- At the end of the fall ENGR 98A course, just prior to the Guatemala experience;

- Upon returning from the EA Guatemala experience; and

- At the end of the spring reflection semester meetings at the conclusion of the EA program.

1) Prior to the Guatemala Experience

The delegates expressed a great deal of confidence in, and commitment to, engineering. Merely having been selected for the EA program and having gone through a majority of the planning phase appears to have boosted their self-confidence and strengthened their resolve to both pursue an engineering degree and pursue engineering as a profession.

“The fact that I was chosen for EA made me feel oh my God I can do this. It gave me confidence that I can be there, do it.”

The students described themselves as ‘tinkerers’ who enjoy understanding how things worked, taking things apart, and putting them back together again. They described that the strong encouragement they received from family and close friends contributed significantly to their educational path. All three cohorts were consistent in their description of engineering as a helping profession, explaining that their interest in the field was rooted in their desire to improve people’s lives. The students credited this to the engineering faculty at Cabrillo who created an environment that is extremely student-focused and supportive.

“The teachers make you feel at home,” one student said. “They emphasize that engineering is a helping profession so we help each other – students and faculty.”

Another student explained “….it is all the instructors, the tutors, the design projects and the team work. I made the connection between engineering and helping people when I came to Cabrillo.”

The EA participants described the fall preparation as a serious time commitment but one that clearly bonded them. Further, even though they have only just completed the EA planning phase, students agreed that EA made them feel they are part of a team. This was particularly true for the 2014-15 cohort who unlike the other cohorts, were also taking many of the same courses.

One student commented that EA’s team building and teamwork revealed that “everybody has something to bring to the table.”

Other students noted that their EA participation created in them a desire to become engaged in other projects, particularly in community projects and volunteering, and inspired them to join and even create clubs. “When I was accepted to EA, we started Latinos United in Cabrillo in Engineering and Science. (LUCES).” The club visited elementary and middle schools in under-represented and low-income areas to get them excited about STEM early on in their lives.

Pre-experience meetings were valued and perceived as a way to introduce the EA students to a new culture and delve into global awareness and logistic arrangements.

2) After Returning from the Guatemala Experience

Despite having prepared for the experiences by developing preliminary work plans in the fall ENGR 98A course, the teams found themselves adapting quickly based on the site conditions and emerging information. The limited timeframe and resources available in the rural village meant that they had to manage the project and timeline carefully. What appeared to be a herculean task was made achievable by dividing the project into sub parts and pairing projects to smaller teams based on individual interests and strengths. Not only did this pair team members with tasks that suited their skills, it ensured that all the team members were involved and felt that they had something important to contribute. Latino delegates were able to step into leadership roles as culturally competent translators and reported a strong sense of pride in being able to bridge this gap for their teams.

“Being one of the few who could speak Spanish made me become more of a leader”

Despite a language barrier, the Guatemala experience provided all the delegates with valuable lessons in client relationships and communication. Another theme highlighted by the various focus groups was the discovery that engineering projects can be designed and implemented in different ways and that there is often not one right answer or a single way to move forward. The delegates explained that this experience gave them the opportunity to apply mathematical concepts they had learned in their classes to the real world and that for many of them, it changed the way they conceived of some of the seemingly remote concepts they had learned in school. This hands on, applied, approach boosted their confidence in their abilities, taught them tangible construction/engineering skills, and gave them a new perspective on their education.

“The water went shooting off in all directions because we were off by one degree [with our calculations]. Something as simple as that can make a big difference. It is the real life side of what we study and you see it coming together and that they [the faculty] did not just tell us to learn this to torture us.”

The students also echoed a strong sense of accomplishment in what they were able to achieve together. They explained how gratifying it was to make a lasting contribution to that community and for the many people, especially the children, they got to know over the course of the project. The experience appears to have reinforced their interest in engineering as a profession and their concept of it as a helping profession.

“Seeing the smiles on the kids’ faces because of something we had done to make their lives better. I mean what more could you ask for? This meant a million times more to those smiles, than some boss telling me I did a good job or finding an engineering job that makes a lot of money. This is what I want to do as an engineer. Make things better for other people.”

“This is what I want to do for a living. I want to work with others and do something to make things better here or in another country.”

3) After the Conclusion of the Program

The Engineering Abroad program appears to have had lasting benefits beyond lessons learned and confidence built during the two-week experience. In the semester following the experience students reported a strong sense of comradery with their EA peers. They described situations in which this new support system had helped them get through difficult courses, made their educational experiences at Cabrillo more enjoyable, and gave them a greater sense of belonging. Upon their return students approached their coursework with refreshed determination. Understanding how the subject matter could be useful or applicable to the real world gave them a new perspective.

“Now, when I take it again, I will really want to learn it not for the grade but because I now see how useful it is.”

The students reported that the activities that followed the experience in the spring semester increased their confidence and comfort level with public speaking, networking, and pursuing internship and employment opportunities. The students spoke of spending long hours working together to develop and practice their presentations.

“Presentations and working together on a poster really increased my confidence – we work way better as a team from coordinating all the presentations we had to prepare.”

They agreed that they had approached their assignments with some trepidation and concern about having to speak in front of professional engineers.

“Before, I had dreaded the idea of networking and all that. But it ended up being easy to talk to all the people there.” “It was not as scary as you think to talk to professionals.”

The EA delegates who attended and presented at the national engineering conferences described the profound impact these experiences had on increasing their confidence and on inspiring them to set new and higher goals for themselves. The post-Guatemala presentations and especially the poster session had made them think for the first time that graduate school may be an option for them.

“I have never been to a conference before where people are doing graduate work. [The conference] opened my eyes and now I’m considering going after a Master’s Degree or even a Ph.D.”

All the presentations were all very well received and contributed to a demystification and accessibility of the world of professional engineers both those who are working for academic institutions and those working in the field.

The students also described having closer and more substantive relationships with faculty who could provide them with not only strong letters of recommendation but with connections to other faculty at transfer institutions and/or potential employers. The participants reported being more successful at securing job interviews and, as a result, they were becoming more comfortable interviewing.

“I have been looking for a job for a long time but when I was able to put EA on the resume…since doing that I have gotten way more call backs. I have had four interviews this far and all have gone well.” One student spoke of recounting her EA experience during an interview. “The interviewers were really impressed,” she said.

Students expressed a strong interest in identifying and pursuing scholarships, to support them after transfer. Several students applied for, and at least one of them reported receiving, scholarships. “I got two scholarships, “one female student reported with a huge smile. “If it hadn’t been for EA, I would not even have considered applying but now I felt proud to fill out the application.”

Other students noted that their EA participation has resulted in them becoming engaged in other projects, participating in community projects and volunteering, and inspired them to join or even create clubs. The students also reported greater involvement with student government upon their return.

“Our life views have expanded – in terms of what we can do as engineers and what we can do here on campus“

Alumni Survey

EA alumni from the first and second EA cohorts were surveyed in April 2016. The survey found that the EA experience continues to influence, inspire, and guide the delegates one-two years after they concluded the EA program. More than 90% of survey takers agreed that EA will influence their career choice and past participants reported overwhelmingly that EA has had a very large impact on their desire to use their engineering skills to help others, locally as well as globally. EA also opened participants’ eyes to the possibility of graduate school and increased their motivation, confidence and motivation to complete their studies. A very large number of EA alumni described career goals in green technology, water conservation, and transportation management. Now that the program has just completed its sixth year and the past delegates have transferred to universities and are practicing engineers, the next steps would be to survey all six cohorts.

Conclusion

The Cabrillo College Engineering Abroad Program is now in its sixth year and one of the few engineering abroad programs in the country that serves community college students. It has engaged a total of 75 students in interdisciplinary engineering teams on service-learning projects in Central America.

The EA program has had a very positive impact on students. The program has significant value not only for what students derive from the year of activities (which includes the two week experience) but for what students gain from the community and environment it promotes on campus. Cabrillo College has several supports that contribute to the inviting and exciting learning environment including an USDE-funded STEM Center in addition to our talented STEM faculty. In this way, Cabrillo College is atypical of community colleges in that it situates students with unique opportunities to grow and succeed. It is clear from the many student testimonials that the EA program has changed student outlooks and given them a greater sense of purpose.

“Before this program I was second-guessing myself. I was wondering and thinking I don’t know if I can do this. I was thinking– these classes are hard and what if I get there and become an engineer and I cannot do it. But this [the EA experience] has increased my confidence hugely about becoming an engineer. I saw that I could contribute and that I can do it. I feel I’m in the right place.”

“Being an engineer is being a professional problem solver. Guatemala opened my eyes to not just solving technical problems, but basic problems such as not having water – it made engineering seem more like a helping profession”

Not only has the program had a lasting impact on the Cabrillo engineering student community, it has had a considerable impact on the community of Vuelta Grande. At the onset of the program Vuelta Grande had an existing system that stored roughly 500 gallons of water. After four years, EA has been able to increase their storage capacity by over 20 times. The community now has a system that can hold up to 19,000 gallons of water. The school has running water and the community no longer has to travel long distances for clean, reliable water in dry months. This has vastly improved quality of life in the community and had the biggest impact on the girls whose task it was to get the water. An unintended result of the project is that there are more girls attending school in Vuelta Grande.

###

Tagged Cabrillo College