Featured

Veteran teacher shows how achievement gaps in STEM classes can be eliminated

By James McGirk

UC Santa Cruz

March 7, 2019 — Santa Cruz, CA

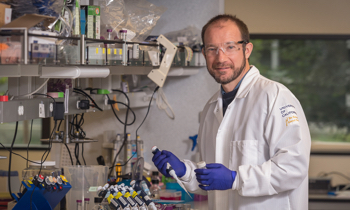

(Photo above: Tracy Larrabee is a professor of computer science and engineering and associate dean for undergraduate affairs in the Baskin School of Engineering. Credit: K. Skemp)

Last quarter, something remarkable happened in Professor Tracy Larrabee’s Applied Discrete Mathematics class. For the first time in her 29 years of teaching, after five quarters of steady improvement and constant experimentation with teaching methods, the gap between the grades of her underrepresented minority and first-generation college students and the rest of the class vanished.

“To have no gap in a class is an amazing achievement,” said Jaye Padgett, UC Santa Cruz’s vice provost for student success. “We’re a federally designated Hispanic-serving institution, which means not only that we serve an underrepresented community, but also that we have a philosophy of equity in our teaching practices. Professor Larrabee is manifesting that philosophy. We’re trying to eliminate gaps and get everyone the best education they can have.”

Larrabee, a professor of computer science and engineering and associate dean for undergraduate affairs in the Baskin School of Engineering, teaches Applied Discrete Mathematics (CE16), a prerequisite for some of the most sought-after majors available to UCSC students, including computer science, computer engineering, and electrical engineering.

The material in her class can be grueling, and the large lecture format (approximately 400 students are enrolled in her class) is intimidating for some students. Scoring below a C means a student must halt progress in his or her major to repeat the class or switch majors to something else. Passing offers tremendous opportunities: Graduates of UC Santa Cruz engineering programs routinely land good jobs in the Santa Cruz and Silicon Valley tech industry and beyond.

Three-pronged approach

Larrabee credits valuable support from two on-campus tutoring programs, the Academic Excellence Program (ACE) and Modified Supplemental Instruction (MSI), and says she uses a three-pronged approach to support underrepresented students in her class.

“The first is that we have had a very diverse teaching staff,” she said. “We have one professor, four TAs and four MSI tutors, and during this time it just happened that of those people, half were female, we always had at least one African American, one Latinx, and one non-gender conforming tutor so that everyone could feel a connection to someone on the teaching staff.”

“Another technique I use is to emphasize failure as the appropriate path to learning,” she said. “Engineering is hard; it’s good to fail the first time you attempt a problem. People who fail at a problem the first time tend to retain things better than those who luck into the right answer.”

In practice this means she won’t take points off on the homework for coming up with the wrong answer. “You just have to try,” she said. “But those problems will probably show up on the weekly quiz that is graded, so it’s your responsibility to learn how to do them.”

To help them do this, Larrabee makes it as easy as possible to get help, even for introverted students. She peppers her course websites with videoed lectures and links to Khan Academy and other sources of outside help. She also makes herself available. “I have plenty of conversation with my students, I keep four online forums going, and try to write to them as much as I can,” she said.

Stereotype threat

Her final tactic is to explicitly discuss stereotype threat. This is the risk that someone (i.e., from an underrepresented minority) might take routine negative experiences as confirmation that they are fundamentally unsuited for something like higher education.

“One of my African American MSI tutors—who are extremely high achieving students selected to provide supplemental tutoring to others—told me it was like having a light bulb go off for him,” Larrabee said. ”Until I discussed the issue in class, he felt like he didn’t belong in this major, but after we talked about stereotypes, he realized it wasn’t that he was unsuited for the material. It was hard for everyone!”

Vice Provost Padgett agrees stereotype threat is a huge issue. “Grade sensitivity, for example, is a big problem. Some populations are predisposed to take things differently. The danger is that you fail your exam and instead of thinking it’s a sign you need to spend more time studying, you take it as confirmation that you’re in the wrong place and you drop out.”

The Baskin School of Engineering has had other successes in bringing disadvantaged populations closer to parity. The Multicultural Engineering Program (MEP), which serves approximately 281 of the school’s 4,234 declared undergraduate majors, has closed the gap significantly.

“There is a strong statistical significance difference between the GPAs of MEP and non-MEP first-generation college students,” MEP Director Lydia Zendejas said. “The average GPA of first-generation, non-MEP students is 2.90 and the average GPA of MEP students is 3.14.”

Larrabee has a few other teaching tricks too.

“In debugging there’s a concept called ‘rubber duck debugging,’ where you get a duck, place it on the terminal and explain things to it out loud in very simple terms, and you often come to the right conclusion… which is to say that teaching one another really helps the learning process. I also try to be as approachable as I can,” she said. “I describe the failures I had as a student, and I’m mildly outrageous in class—it helps break the ice and break up the monotony; they’ll laugh, and if they’re awake they’ll learn and will feel more comfortable coming to me or one of the TAs with questions.”

Teaching councils

Larrabee has also made use of many of the interdisciplinary teaching councils on campus such as the Center for Innovation in Teaching and Learning (CITL), which provided reinforcement for Larrabee’s emphasis on stereotype threat and helped her to incorporate more active learning techniques into her lecture style.

Some other insights she’s found helpful: “People need to use their bodies to learn,” she said. “Handwriting is a different neurological thing than typing. It gives people time to process what they’re learning while they’re writing, So I make sure that all my homework is handwritten and, when I lecture, I make nice slides and I use a stylus to scribble all over them.”

Larrabee is currently putting together a proposal for the National Science Foundation’s Revolutionary Educational Design program that will attempt to replicate her success by proposing a series of interventions to keep STEM students on track and enmeshed.

Larrabee says she became a professor to help increase the representation of women in academia. “I’ve been teaching for 29 years,” she said. “Only recently have I closed my equity gap. I’ve been constantly working to improve: CITL’s help and the CITL community have really helped me incorporate more active learning.”

There’s a long way to go, but perhaps a path to parity is emerging.

Originally published here: https://news.ucsc.edu/2019/03/larrabee-equity.html

###