Companies

New $53 million grant to create a world-wide fleet of robotic floats to monitor ocean health

(Contributed)

November 3, 2020 — Moss Landing, CA

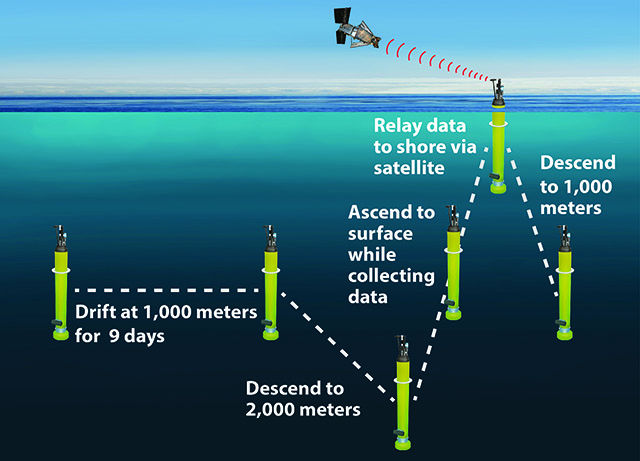

(Image above: This illustration shows how biogeochemical floats spend most of their time 1,000 meters below the surface, then collect data and send it back to shore via satellite every 10 days. Image: Kim Fulton-Bennett © 2020 MBARI)

On October 29, 2020 the National Science Foundation (NSF) approved a $53 million grant to a consortium of the country’s top ocean-research institutions to build a global network of chemical and biological sensors that will monitor ocean health. Scientists at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI), University of Washington, Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Princeton University will use this grant to build and deploy 500 robotic ocean-monitoring floats around the globe.

This new network of floats, called the Global Ocean Biogeochemistry Array (GO-BGC Array), will collect observations of ocean chemistry and biology between the surface and a depth of 2,000 meters (6,560 feet). Data streaming from the float array will be made freely available within a day of being collected, and will be used by scores of researchers, educators, and policy makers around the world.

These data will allow scientists to pursue fundamental questions about ocean ecosystems, observe ecosystem health and productivity, and monitor the elemental cycles of carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen in the ocean through all seasons of the year. Such essential data are needed to improve computer models of ocean fisheries and climate, and to monitor and forecast the effects of ocean warming and ocean acidification on sea life.

Although scientists can use earth-orbiting platforms and research vessels to monitor the ocean, satellites can only monitor near-surface waters, and the small global fleet of open-ocean research ships can only remain at sea for relatively short periods of time. As a result, ocean-health observations only cover a tiny fraction of the ocean at any given time, leaving huge ocean regions unvisited for decades or longer.

A single robotic float costs the same as two days at sea on a research ship. But floats can collect data autonomously for over five years, in all seasons, including during winter storms, when shipboard work is limited.

Funding for the GO-BGC Array is provided through the NSF’s Mid-scale Research Infrastructure-2 Program (MSRI-2). The GO-BGC Array is the National Science Foundation’s contribution to the Biogeochemical-Argo (BGC-Argo) project. It extends biological and chemical observing globally, and builds on two ongoing efforts to monitor the ocean using robotic floats, both of which have been highly successful.

The first of these programs, the Argo array, consists of 3,900 robotic floats that drift through the deep ocean basins, providing information on temperature and salinity in the water column. Since its inception in 1999, Argo data have been used in 4,100 scientific papers. As the first global, subsurface ocean observing system, the Argo array has done an incredible job of measuring the physical properties of our ocean, but Argo floats do not provide information about the ocean’s vital chemical and biological activity.

Starting in 2014, the Southern Ocean Carbon and Climate Observations and Modeling (SOCCOM) program deployed a large array of robotic “biogeochemical” floats, based on the Argo design, but carrying sensors to monitor the chemical and biological properties of the ocean. SOCCOM floats have operated for nearly six years in the remote, stormy, and often ice-covered Southern Ocean—arguably one of the harshest marine environments on Earth. These floats have already provided critical new information about how the Southern Ocean interacts with the Earth’s atmosphere and winter sea ice.

Continue reading here: https://www.mbari.org/go-bgc-release/

###

Tagged MBARI